Pasteur’s timely message for rigour and relevance

Author: Barry Rogers

Just like Monsieur Pastuer can I ask you to do a simple experiment?

Type the word ‘scientist’ into any search engine. Press images and see what comes up.

I would be very surprised if you did not see lots of earnest young professionals, sterile labs, white coats and half-filled test tubes.

For many of us this is what science ‘is’ – controlled experiments in neat, controlled settings. Yet my scientific world looks nothing like this. For one thing, it is social in nature and a million miles from the reified setting of a sterile Lab. As a ‘pracademic’ the idea of control for me is something of an illusion. My Lab operates at the intersection of a university and the real world; an interface where the production of knowledge is as much about messy relevance as it is disciplined rigour.

There is a profound issue however with a narrow understanding of science. Seeing science this way actively limits the legitimate space in which scientific knowledge can be produced and consumed. At this moment in human and non-human history that perspective is very dangerous. More about that in a bit.

First. How might we see scientific activity beyond a narrow lens?

Enter Donald Stokes. Stokes (1927-1997) was an American political scientist with a deep frustration around how science, as a process, was seen to ‘work’. He challenged the idea that elite knowledge e.g. fundamental/basic research, was the only ‘proper’ knowledge and that those that operated downstream of this were engaged in a lesser, derivative activity (e.g. technical application). This linear representation of science, deeply engrained since Aristotle, largely guides the working of public science policy.

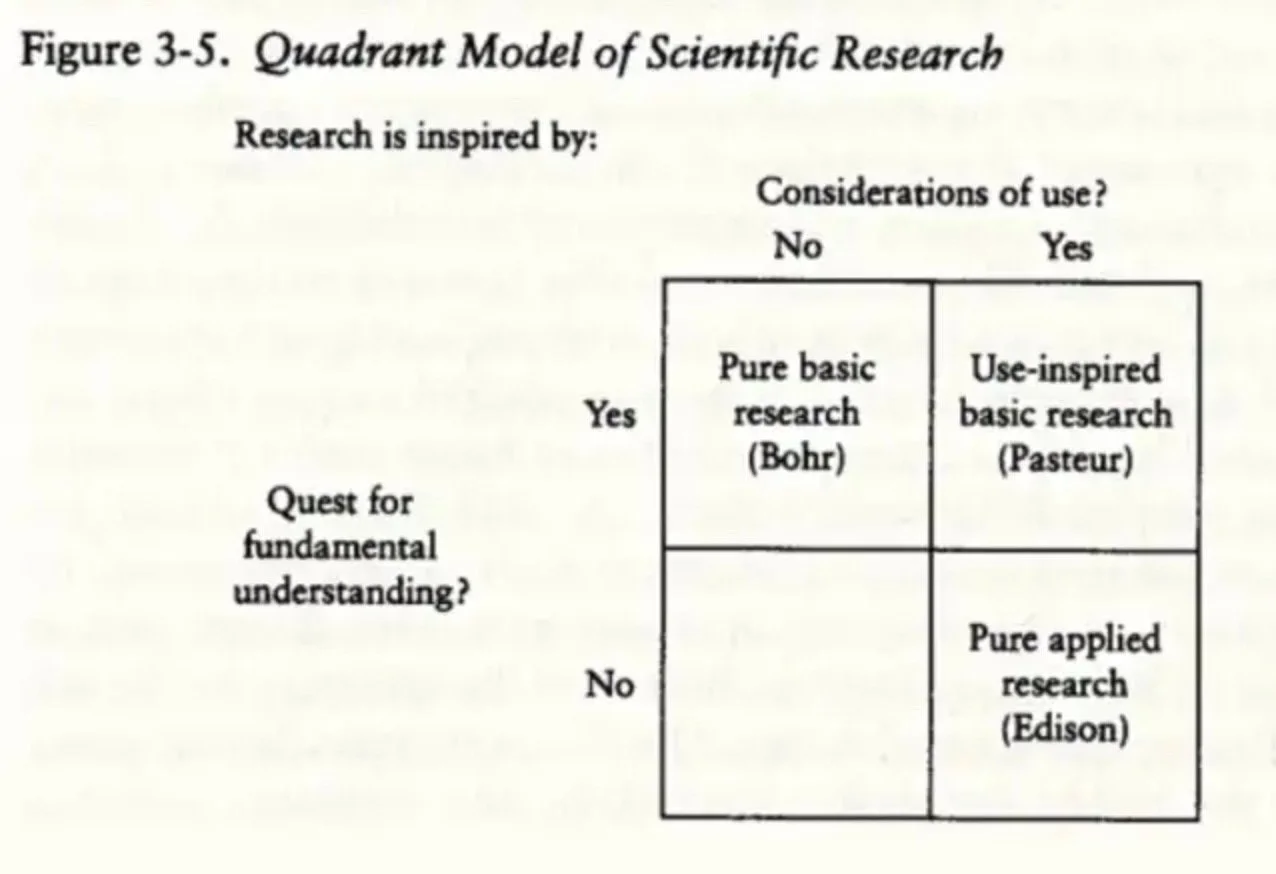

Stoke’s articulated his alternative approach in the book ‘Pasteur’s Quadrant’ (1997). Here he rejected a linear approach to pure and applied research suggesting instead a four-quadrant model that incorporated the logics of both rigour and relevance: his metrics for these logics were low to high considerations of understanding and use. This original ‘Quadrant’ model outlined by Stokes is seen below.

To bring his model to life, Stokes populated three of the four quadrants with a scientist that personified the logic of that box. Straddling high understanding and low use was the physicist Nils Bohr. This quadrant symbolised the pursuit of pure, basic knowledge; ‘breakthrough’, abstract thinking that someday, somehow might make its way to end-use. In (Thomas) Edison’s quadrant the focus was on applied research; an activity that lacked a highly distinctive contribution to new knowledge but was hugely useful. In the top right-hand corner, at the intersection of high use and high understanding, was the chemist Louis Pasteur. Here was the domain of use-inspired ‘basic’ research; something that is deeply practical but also seeks to answer fundamental questions in novel ways.

Pasteur’s quadrant has guided my career; I have located myself as a scientist in this quadrant. For me the binary distinction between rigour and relevance has always felt hugely simplistic, overly reductionist and just, plain wrong.

But there is more. The binary distinction between scientific rigour and relevance is not just simplistic it also feels ominously dangerous, especially at this moment.

For centuries sophisticated, abstract thought was the driver for many of the advancements in society and humanity. Much of this knowledge was generated in and around our great universities. In the parlance of economics these institutions were monopoly providers, existing with little meaningful competition. That luxury has disappeared. Universities now operate in a crowded epistemic marketplace; one where authority, speed, relevance and legitimacy no longer align automatically.

The core offering of a university, largely unchanged for nearly a thousand years, is increasingly disintermediated by LLMs. The creation of elite, sophisticated knowledge, until recently the preserve of time-intensive ‘upstream’ activity, has serious competition. Relatively inexpensive bots can deliver PhD-like insight in an understandable, useful and ontologically sensitive fashion in a fraction of the time, and at a fraction of the cost. Alongside this, the legitimacy of how we produce knowledge is challenged by complex cultural entanglement. Many leading institutions find their social license to operate under threat, just ask anyone working in and around institutions like Harvard, Columbia or Stanford.

The message is stark. The proposition surrounding what we as academics do, and how we do it, needs to change. Unless we allow ourselves to think differently about what science is, and, most of all, where rigorous, relevant, breakthrough knowledge is produced, the future feels like a darker place. Universities risk irrelevance at precisely the moment society needs them most.

Sitting on the remote Mountaintop of understanding is no longer an option. Meaningful engagement in Pasteur’s Quadrant is a way of thinking about the evolving space for science. I suspect we overlook it at our peril.

[Postscript: In a forthcoming piece I will explore what meaningful engagement within Pasteur’s Quadrant actually looks like in practice]

Update note: Title and subtitle 14/1/2026

Selected readings

For more on the grounding for a linear understanding of science in public policy:

Bush, V., & R, U. S. O. of S. (2022). Science, the Endless Frontier; a Report to the

President on a Program for Postwar Scientific Research. Legare Street Press.

For more on operating in Pasteur’s Quadrant as a pracademic:

Rogers, B. M. (2025). Beyond the illusion of change: Bridging the ‘classroom’ and the

workplace via processes of temporal re-contextualisation. Proceedings of the Paris

Institute for Advanced Study, 2 . https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14729747

For more on the foundational background to Pasteur’s quadrant:

Stokes, D. E. (1997). Pasteurs Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation.